A.

Everything — the ground, the leaves, the walls — damp with morning dew. The birds, so loud, not a chorus but a riot, a flash mob of birdsong. You are nearly blinded by the shimmer of the grey world.

It's all coming through you in a flood. On the one hand, you could feel guilty for the excess — the indulgence! But on the other, you might accept that you are powerless against this grace, and ride the wave until it inevitably recedes. You are a vessel, and this is not about you. (Though of course you want it to be.)

And it is about you.

You remember the ugly orange carpet, fibers fuzzing up in whorls, don’t you? The one you learned to crawl on? It was like this then. A rush of feeling and sound, and the smell of wet rice, and what is this and how do I, and the weightlessness of transition.

You remember shrieking as you fled from the inflatable kiddie pool, docked in the shallows of a dry grass ocean; shrieking, because a bee dared to sting while you were cooling off from the thick, hot stillness of summer. You remember the beautiful battery-operated puppy with curly white fur that could walk across the carpet, so cute and awkward you almost believed it was real.

Everything is real now. That is the blessing and the curse of growing older. You are trying to catch what you can in a net you are weaving of words, because you know it all goes — the good, the bad, the beautiful.

B.

Your father dreamed like this: in long stretches of lyric and melody, downstairs, late into the night. You fell asleep to his voice crooning softly over piano chords, or to the contemplative wail of the saxophone (and when it was the saxophone, it was always from the basement, with the door closed — your mother needed her children to sleep).

Sometimes, he got started before it was time for bed and played a tune for you and your sisters to jump around to, accelerando and crescendo until the three of you were giddy and breathless with whirling around the room.

He must have been tired after a long day of work and shuttling ballet dancers and violin students and gymnasts; still, he descended the stairs to practice after dinner and found something like a reason. A doorway to himself.

You wonder what doorway your mother had. Maybe, after working all day herself, and mothering three children and making dinner and maintaining an orderly home with four messy housemates, she had no use for a doorway — what she needed was a bed.

You wonder whether your father was swept up in a flood those nights, blinded by the shimmer. Whether he was a vessel for something only he knew had to be birthed. You wonder whether he felt guilty for the indulgence.

You think: we are all just trying to catch what we can before it goes.

Craft Notes:

The title of this composition refers to the musical definition of counterpoint*: “The combination of two or more independent melodies into a single harmonic texture in which each retains its linear character.” Merriam-Webster, merriam-webster.com/dictionary/counterpoint

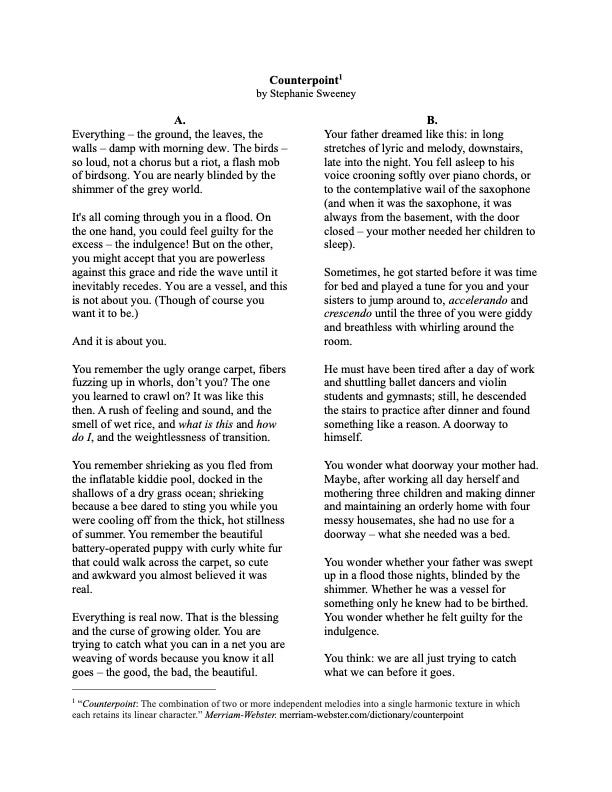

I intended for sections “A” and “B” to appear as two columns of equal length side-by-side, but Substack doesn’t allow for columns. Here’s an image of what it should look like.

*If you care to share, I’d be interested in your thoughts on whether the explanation of the title adds anything to your reading of this piece. I considered putting the definition as a footnote to the title, or in the heading, or just leaving it out altogether. This definition is important to me, and I sort of liked the idea of making it part of the piece in some way, but I don’t know that the reader needs it!

I recently read this piece by

, which linked to this essay by Lydia Davis writing about a painting that was significant to her. In her essay, she describes how learning the subject referred to by the abstract painting changed her experience of it (though she does not say it added to her understanding of the piece; in fact, the opposite happens.) The conclusion (if you can call it that) seems to be that “part of the force of the painting was that it continued to elude explanation.” Grant writes in his post about writing toward the memory of a work, and not needing to solve everything. (Highly recommend reading his post, it’s a good one.) Reading those essays together got me thinking about what we might know about a piece, what choices the artist can make about how much to explain, and how that information, or the absence of it, can alter the experience of a piece for better or worse. Let me know if any of this is something you have thoughts about, too!

I’m awestruck. “You are trying to catch what you can in a net you are weaving of words, because you know it all goes — the good, the bad, the beautiful.” –– It’s the impossibility, the futility of it that makes us mad as writers, as aging humans. Yet we keep trying with, sometimes, success. And here, you’ve nailed it by letting us peek at your memories, real or fabricated. You’ve let us behind your eyes to see the colors and shapes as only your words can. We see the pool in the yard, the stairwell to the door, hear the music echoing through the house after everyone is in bed. Even the tiredness of a mother who doesn’t seem to have the solace of her own space.

The two pieces work beautifully together, read in sequence or bounced back-and-forth. They’re really just beautiful

I didn’t think much of the title until I got to the second part in reference to music — I really like that.

The whole juxtaposition of the two pieces was well done. Part A especially was a delve into memory and nostalgia that I love.